Frisch’s Big Boy, a local Cincinnati Restaurant chain, was purchased by National Restaurant Developers (NRD) and taken private in 2015. As part of this transaction, NRD used Frisch’s own buildings and land as collateral to finance the transaction and store remodeling. After Covid, Frisch’s struggled to cope and was eventually served eviction notices in 2024. We review the transaction and strategy, and the lessons that can be learned.

Author’s note: My dad recently passed away in August. He used to love going with my mom and family to Frisch’s every Sunday after church. They had their favorite waitress—Chanel—who always made them feel incredibly welcome. Dad worked in finance and accounting for much of his career and I hope he would enjoy the analysis. This article is written in memory of my dad and for all the employees of Frisch’s who have seen their livelihoods imperiled by their recent eviction.

Table of Contents

Background

David Frisch started Big Boy in Cincinnati, OH in 1946. It was essentially a rebranding of his existing diners from a California franchise. The franchisor charged Frisch’s a paltry $1 per year franchise fee. By 1950, a 150 Frisch’s Big Boy diners had popped up across the Midwest, mostly centered in Ohio. Frisch’s Big Boy was known for its double decker hamburgers and signature tartar sauce, as well as vanilla flavored Coca Cola. Frisch’s also appealed to Cincinnati’s predominantly Catholic market with its Lenten fish and tartar sauce specials.

In 1989, the grandchildren of David Frisch—brother and sister Craig and Karen Maier—became CEO and Vice President of Marketing, respectively. On one hand, the company generously supported local arts and charities. On the other, it continued the fiefdom mentality of the 80s with investments in unrelated businesses, such as a stake in the Cincinnati Reds, a horse farm, and two hotels. In the 1990s, the two local activist investors Barry Nussbaum and Jerry Ruyan purchased a 7% stake in Frisch’s. This was aimed at forcing the company to focus on its core business and ultimately compelled operational improvements such as the implementation of a point-of-sale system. Nussbaum and Ruyan were not to be the last activist investors.

In 2012, the Maiers had ended an expansion of Frisch’s through the licensing of Golden Corale Buffets by selling 35 franchised stores at a loss. This was the latest in a string of failed attempts to diversify and grow the company.

By 2014, Frisch’s Big Boy was operating 95 corporate stores and 26 franchises. The number of restaurants remained unchanged between 2011 – 2015 and sales was growing at a rate of about 1% per year. The company was traded publicly on the AMEX stock exchange and traded at a nadir in 2013 at $16.32 per share. Consumer preferences also started shifting towards healthier foods. Needless to say, Frisch’s struggled to adapt with their burgers and chocolate cake.

By the time the Maiers were nearing retirement age, they owned 16% of Frisch’s combined, and seemed to be searching for a way out. No one else in the family seemed ready or capable of taking over the company. Moreover, the treasurer of Frisch’s embezzled a whopping 3.3MM USD, and one of its auditors, Grant Thorton, issued an adverse opinion on its financial controls for FY2014 (a bit too late after the embezzlement already happened!)

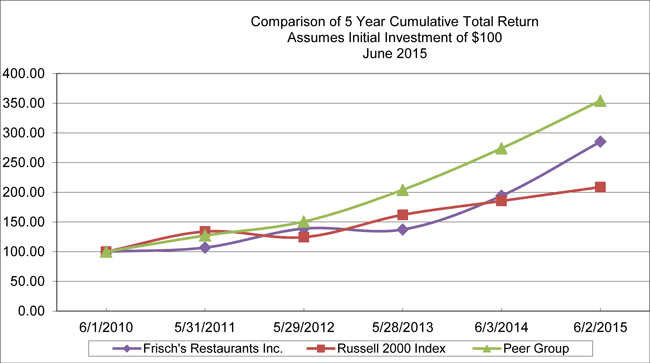

In 2014, an activist hedge fund—AOF Management—took a 5% stake and began to exert pressure on the board in an attempt to show better returns for investors. The stock price climbed to about 25.00 per share because of the activist investment and rumors of a potential sale.

Frisch’s Financial Price in 2015

To try and understand both the financial structure of Frisch’s and the assumptions driving their stock price, I reviewed financial statements prior to 2015. About 95 corporately owned restaurants existed back then. These corporately owned stores averaged sales of about 2.2MM USD per year, and had cost of sales of about 89%, which left about 240K USD per year in gross margin per store. A total of 25 franchise owned stores contributed on average about 55K in net per year. SGA was a very low 7% of revenue. Net operating profit after tax sat at 4.2% or 8.8 MM USD per year. Store counts were flat and revenues were slowly increasing by 1% per year.

Frisch’s owned the land and buildings for almost all its corporate stores—this will become crucial later on. Like many restaurants, Frisch’s was working capital negative—that is, they were receiving payment much faster than what they were paying their vendors. By 2015, Frisch’s had almost no debt, had about 11MM USD in operating leases, and had a healthy balance sheet.

Putting all that together, I estimate a stock price of about $18.81 per share in 2015, which is in the right range compared to the pre-Activist investment market price of $16.00 – $19.00 per share in 2013. Finally, this valued Frisch’s as one entity in the restaurant business as it stood at that time.

The Buyout

At the beginning of 2015, Frisch’s announced a deal with NRD—a private equity firm that specialized in restaurant turnarounds and rebuilding. The deal was for $34.00 per share on 5.1 million shares, or $174.5 MM USD in total consideration. Another key piece of information is that, back then, the land and buildings owned by Frisch’s were turned and sold to a third company called NNN Reit, Inc., who then leased the properties back to NRD.

With NNN’s recent forced eviction of some of Frisch’s locations, the leaseback transaction can now be better understood via court documents and NNN’s own financial statements. NNN paid about $167MM USD to NRD for the properties. NRD netted $165 MM USD after transaction fees. NRD then put up $9.5MM USD of its partners cash to make the total of $174.5MM USD in consideration. NRD and NNN entered a 20-year lease where NRD paid $12MM USD per year for the use of the properties.

The key here is that NRD used only 9.5MM of its own cash and levered the properties it acquired from Frisch’s to make up the rest of the 175MM purchase price.

Another thing is that NRD paid a much higher price—$34.00 per share— for Frisch’s than its stock market value—$19.00 per share—would suggest. The $34.00 valuation only makes sense if the land and buildings are viewed as one business and the restaurant is viewed as a second business. When I separate them, I get $5.73 per share for the restaurant and $32.54 per share for the building and land. That is, the land is much more valuable than the restaurant on which it sits. Are they really two separate businesses though?

So: NRD now owns Frisch’s (the restaurant), and is leasing the land and buildings from NNN. What’s next?

Building a New Frisch’s

NRD’s plan was to grow and modernize Frisch’s. They first brought in a new CEO — Jason Vaughan — who had been at Wendy’s and Yum Brands, and who then did a turnaround at Lenny’s Subs. NRD and Jason created a plan to update the brand image and menu, to expand the store counts and franchisees, and to update the outdated store interiors.

Then, in 2018 NRD increased its leverage with NNN by remodeling Frisch’s to make key stores more vibrant and with an updated image. In this addendum, NNN paid $150k per store to NRD for remodeling 40 stores in exchange for increasing the rent at each of those stores by 7%. After the first store remodelings were successful, they signed another agreement in March of 2020 with the same T’s and C’s for another 40 stores—a very inauspicious moment.

The strategy now becomes clear—NRD was using the land and buildings as a giant piggy bank to finance the turnaround of Frisch’s while NNN held the land as collateral and charged NRD a market rate rent. However, NRD and NNN still faced lots of joint risks and joint upsides. NNN could only really be successful if NRD was successful in its turnaround of Frisch’s, and they were locked into a long term lease together.

Everything continued apace until…

What went wrong at Frisch’s?

In 2020, COVID happened, and the world went into lockdown and altogether avoided eating out. The first effect was that Frisch’s no longer had any customers for most of 2020, and even fewer customers in 2021 and 2022. The second effect was that it became harder to staff restaurants during this period—both due to turnover from the pandemic and an extraordinarily tight labor market. The third effect was that inflation took hold, mostly due to over stimulus by the Trump and Biden administrations, as well as the Federal Reserve’s money policy that was just too loose. Inflation is hard for three reasons. First, inflation disproportionately affects Frisch’s customer base, making them less likely to dine out. Second, the price of labor and food goes up significantly. Third, the rent paid to NRD by NNN is inflation adjusted, but the adjustment didn’t take effect until 2021. Thus, NRD saw an already unpayable rent bill grow even larger in 2021.

NRD and NNN initially responded to the challenge of COVID as partners. NNN agreed to reduce rent from April 2020 – Jun 2020. They would continue to add additional agreements through September 2020, as well as December 2021, to reduce the rent. Unfortunately, such patience would not be indefinite.

By 2021, it become clear that NRD/Frisch’s was in trouble. NRD started closing stores and sold 10 in 2021, with about 15 more between 2022 and 2024. In February of 2024, NNN first sent a complaint for nonpayment of rent on the remaining 73 stores and then filed a vacate notice in September of 2024. By the time of writing of this article, former NRD managers are trying to buy some stores, but most of these will likely close.

Who won and who lost?

Who wins?

Sadly, this story doesn’t have many bright spots.

The original shareholders of Frisch’s

The original shareholders of Frisch’s, who invested between $19.00 and $25.00 per share, made a significant gain on the $34.00 sale price. Among them are the Maier family who cleared around $28MM USD in total. AOF, the activist shareholder, also did well. If they entered at $19.00 and exited at $34.00, then they would’ve seen a gain of $3.8MM USD. Of course, any other institutional or retail investor would’ve also seen a significant gain. They managed to liquidate their position and avoid the buzzsaw of COVID.

Who lost?

NRF

NRF, who engineered most of the deal, did not exit well. They most likely lost all, or most of, their initial $9.5MM investment, plus any legal fees in addition to what they’ll still incur to wind down their stake.

NNN

NNN paid $176MM USD and only collected about $44MM in rent. While they still own the land and buildings, it’s hard to say when, if ever, these buildings will be occupied and provide rent again, or whether they’ll even be able to sell the buildings. Thus, they’re losing on this deal.

Frisch’s Employees

The employees—wait staff, cooks, and managers—still working at Frisch’s in 2024 unceremoniously found themselves without a job, without any warning. The people most vulnerable in this money game are also the ones who come off worst, since they face uncertainty just before the holidays start.

Key Takeaways

(1) Capital Productivity: In the 90s and 00s, Frisch’s capital productivity (measured by ROIC) was already weak. However, ROIC as conventionally defined by accountants doesn’t capture the appreciation of the building and land. In light of this, ROIC would technically be even weaker and should have forced Frisch’s to reinvent itself sooner. This situation becomes clearer when analyzing the company’s price piece by piece versus the price of the integrated whole.

(2) Focus on one thing only: In the 90s, Nussbaum and Ruyan successfully applied the idea that companies should only operate in their core competency and not build conglomerates. Frisch’s investing into a horse farm or the Reds makes no sense unless a public company is viewed as a manager’s personal fiefdom. These guys seemed like they were conscience and sharp in their analysis.

(3) But don’t go to deep: Ample examples exist where investors and stakeholders get burned when trying to separate intrinsic parts of a business. Frisch’s isn’t a real estate company, they’re a restaurant. As such, their losing sight of that fact inherently risked ruin. This mistake is why NNN got burned badly.

(4) Leverage is leverage: Leverage—whether it’s debt from a bond, a loan from a bank, or a sale leaseback secured by property—is still leverage. Leverage increases risks and if a company starts to find itself in adverse circumstances, the chance of bankruptcy increases. COVID burned NRD, but they would’ve had a better chance of survival had they not been so levered.

(5) Be mindful of stakeholders: Frisch’s employees are waitstaff, cooks, and line managers. They aren’t highly compensated software engineers or high-end financiers. Frisch’s failure hit them the hardest.

The financial model is downloadable here:

See my other financial modeling content about the shutdown of Reddit’s 3rd party apps here or ADM’s accounting scandal here. Like this content? Read how firms can respond to the Trump Tariffs here.